Longtime Vancouver Symphony musician and former OCSM Secretary Stephen Wilkes recounts the early labour history of the VSO, from its first CBA in 1966 to a brush with bankruptcy in 1988.

Longtime Vancouver Symphony musician and former OCSM Secretary Stephen Wilkes recounts the early labour history of the VSO, from its first CBA in 1966 to a brush with bankruptcy in 1988.

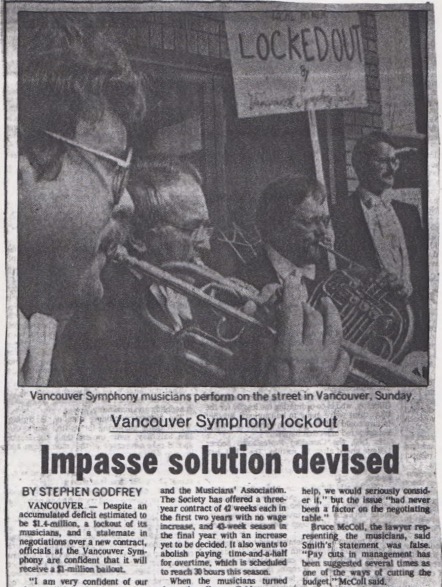

The Vancouver Symphony is not without its labour upheavals, although the musicians had no history of militancy in the early beginnings of their collective bargaining agreements (cba). The orchestra members voted for a strike, bitterly opposed by the Vancouver Symphony Society (VSS) at the start of the 1965-66 season. This was to achieve their first CBA, despite bitter opposition, by the Vancouver Symphony Society (VSS). The result, however, was a three-year agreement which formally structured wages and benefits.

Transitioning to the 1980’s was a difficult struggle as the orchestra became more fully professional as to quality, size, and budget. There was a demand for more information from the Society and for the acceptance of musician input. The view of the management team was that cba’s of that period were “too rich.” Bargaining for a new contract in 1985 saw the musicians with raised expectations due to a new Music Director, who was to start in the fall, along with that of the impending Expo ’86 and its expansive music programme.

1985: Lights out on the Symphony

They were soon to be disappointed with the attitude of the management team, led by a new General Manager, who was a practicing Vancouver attorney as well as an amateur musician. The musicians responded with an attorney retained by the Local, which by then was known as the Vancouver Musicians’ Association (VMA). As the symphony musicians were declared to be employees of the VSS by Canada Revenue in the early 70’s, the musicians’ (and VMA’s) attorney suggested that application be made to the Provincial Labour Relations Board for certification as a bargaining unit, i.e., the VSO full time members become a full-fledged labour union. This advice was taken by a formal vote at the end of the ‘84-85 season.

At the start of the new ’85-86 season, the musicians were told to report to the concert hall with their instruments and to be prepared to rehearse the first programme of the new season without a contract. Upon arrival, the entrance area was flooded with every media type and TV cameras from Vancouver and even some US cities. As the orchestra members arrived, they were told to go upstairs to a meeting room for a vote. As everyone was assembled, the musicians’ attorney announced that an offer from the management would be put in motion for a vote. “However, I must tell you that I do not advise you to accept this agreement,” he said. “There is a possibility that you may be locked out.” The orchestra voted to reject the offer, and the lawyer left for his discussion with the VSS negotiating team.

When the attorney returned, he informed the musicians that the VSS had indeed declared the orchestra to be locked out.

“Do you get that?” he asked. “You are locked out - but you’re in! Would you be prepared to sit in your places and be ready to play? If asked by a peace officer, would you leave promptly and quietly?”

As light travels, so did the musicians scramble down the stairs to their chairs on stage.

“Why are you here? You are locked out,” said the VSS chief negotiator.

“We’re willing to play and talk,” answered the musicians.

“Yeah, why don’t you let them play?” chimed the media: clicking, recording, videotaping.

The GM left in a huff.

Then, suddenly, complete darkness.

Cameras, video cameras, flash bulbs popping non-stop and the media, all of them, for the sake of balanced reporting, still chirping the VSS GM, though he had left for his office in the Society’s enclave below the public theatre entrance. Headlines the next day showed:

“Lights out on the Symphony.”

The VSS never had a chance to address its views to the public or to state its case in any form. The public just retained the image of a blackened stage on the newspapers and TV screens. They could not match the tactics, skill, and connections of the VMA/VSO attorney, who later Became a Justice in the Supreme Court of British Columbia.

The lockout lasted eight days, then the two sides made peace - not the everlasting kind, but that of a utilitarian practicality that concealed the pettiness and rancor yet to emerge. The musicians had won the dispute, but to what end remained uncertain.

And in three years time, that uncertainty became concrete.

1988: A brush with bankruptcy

In January of 1988, during the intermission of a pops concert, the Chair of the VSS Board of Directors announced to the musicians that the season was immediately suspended. The Chair cited continuing deficits of the past three seasons along with dwindling audiences. He claimed a 21.5% deficit, sufficient to make the Society insolvent. It remained for the musicians to decide if they were to play the second half of the concert, to which they agreed avoiding any negative perceptions. At the end of the concert, the musicians left the hall tearful, saddened, angry and disgusted.

Immediately, there was monetary relief available to the musicians. The International Board of the AFM, citing that the current collective agreement was still in force, voted to make the Symphonic Services Strike Fund available, to which the VSO was a member at Day 1. The full-time musicians, as employees, were deemed by Canada Revenue as qualified for Employment Insurance. The Local gave the musicians permission to produce their own concerts in various venues. The Orchestra Committee received the entire proceeds from a recent concert of the Vancouver Bach Choir, in conjunction with the VSO, to deal with the oncoming additional expenses, which would exceed its annual budget. The Committee also received generous contributions from OCSM/OMOSC orchestras as well as an ICSOM orchestra from the States.

The Vancouver media throughout all these events showed support for the symphony with fair reporting and poll results – the community’s positive response to the question of the need for the symphony.

An attorney, not connected to the Local, but acting pro bono, attended an early meeting of the musicians and said that the Symphony Society’s use of the term “suspension of operations” would become a “proposal for bankruptcy,” an outcome in which bankruptcy can be avoided should the creditors of the Society, including the musicians, accept the terms. In time, City Hall appointed a Bankruptcy Trustee who had absolute control over the business affairs, including dissolution, of the Society’s affairs.

The Mayor of Vancouver, along with City Hall, became the focal points of the Symphony Society’s reconstruction. The old VSS Board of Directors, who pulled the plug, resigned, and placed their resignations in escrow. To the slogan of “Save our Symphony” City Hall established a community-wide fundraising event. Elementary school children contributed by collecting donations door to door in their neighbourhoods.

The mayor then formed a new board, slimmed down to about six members. The musicians voted for a new Negotiating Committee. The results were controversial as the new team were comprised of mostly Principal players, who in turn countered that the Board negotiators regarded the VSO Principals as the only musicians with sufficient information to proceed into bargaining.

Attorneys were retained by both the Society and the VMA. A 5-year CBA, at that time the longest agreement with Canadian orchestras, was offered by the Society to the VSO members. Of note, the agreement had a wage opener after 3 years and a clause enabling orchestra reduction down to the individual musician.

Fundraising next addressed the federal and provincial governments' financial commitments for the five-year term of the agreement. There was a successful push from the Vancouver Central MP in achieving this.

Around this time, the Meeting of Creditors occurred with successful results. The BC Provincial Government, the largest of the Creditors, forgave the debt of the Society and the VSO musicians accepted a $500 payment each on a half season’s salary.

The VSO then had an underwritten series of high-event concerts including one at the Whistler Mountain top with a piano spectacularly lifted by helicopter to the stage area, and a Barge concert with fireworks.

There were lumps and bruises along the way, including the difficult installation of a stable management team, the replacement of departed musicians and the reestablishment of trust and accountability. The VSO resumed performing regular subscription concerts in September 1988.

Violist Stephen Wilkes was a member of the Vancouver Symphony for 50 years. He also served as OCSM Secretary and Treasurer. This article was excerpted in the November 2023 issue of Una Voce.